The Other China Connection—Dwight Heald Perkins and Nanjing

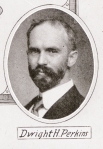

If Walter Burley Griffin had no real connection with China, the same was not true for Marion Mahony Griffin. As students and fans of the Griffins will know, Dwight Heald Perkins, a well-known Chicago architect, was Marion’s cousin. But Walter had a direct connection of his own to Perkins: Walter worked in Perkins’s Chicago office immediately after finishing his degree at Illinois, so he was quite familiar with Perkins and his operations. Consequently, even though Dwight Perkins never designed a building in Grinnell, he was closely connected to the Griffins. And, by virtue of receiving the commission to design the first buildings of China’s Nanjing University at about the same time that Ricker House arose on north Broad Street in Grinnell, Perkins inevitably joined the Griffins in a grand venture of international design.

Dwight Perkins, however, never went to China, nor was he responsible for most of the designs applied to the new university; those tasks fell to his partner, William Kinne Fellows, who spent five months in China in 1914, deciding basic questions of design as well as the best materials locally available. Fellows’s contribution to the Nanjing project, therefore, was enormous. But it was Dwight Perkins who handled all the business of the commission, particularly by his assiduous attentions to Nettie Fowler McCormick, one of the principal benefactors of Nanjing University.

***

Cady & Gregory, University of Nanking Plan (Feb. 1912). University of Nanking Magazine 4, no. 1 (Feb. 1913), cover overleaf.

About the same time that the Rickers moved into their new home in Grinnell, spring 1912, it looked as though the commission for designing the campus of Nanjing University might go to a New York firm. An early plan of the proposed campus, dated February, 1912 and published in the University magazine, bears the name of Cady and Gregory, a well-established New York architectural firm that J. Cleveland Cady headed. By this time Cady, sometimes called the “Presbyterian architect” for his numerous commissions for the Presbyterian church, was 75 years of age and nearing the end of his career. Whether his age affected the commission is unknown, but already in March 1912 another New York firm had entered the picture: Ludlow and Peabody. William Orr Ludlow (1870-1954) was born in New York and in 1892 received an engineering degree from Stevens Institute of Technology. After an earlier partnership dissolved, in 1909 Ludlow partnered with Charles S. Peabody (1880-1935) who had graduated from Harvard in 1903, and in 1908 from Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The firm, which lasted into the 1930s, was responsible for several hundred designs, including many New York City churches and several skyscrapers. But its beginnings depended upon two college campus designs: Sheldon Jackson College (now dissolved) in Sitka, Alaska (1910-11); and George Peabody College (now part of Vanderbilt University) (1911-14).

Nettie Fowler McCormick, 1919. Stella Virginia Roderick, Nettie Fowler McCormick (Rindge, 1956), before 163.

As with Cady, Ludlow’s Presbyterian background (his father was a Presbyterian minister) and his work for the Presbyterian Sheldon Jackson School attracted the interest of the university board. In an April 15, 1912 letter to L. H. Severance, Ralph Diffendorfer, then secretary to the Nanjing University Board, reported that he had been in contact with Ludlow. “I have asked him,” he wrote, “to talk with his partner about the possibility of their willingness to undertake the entire work involved in laying out this property and the various buildings.” Ludlow and Peabody, he continued, “are both Christian men and I have asked them to make this work a contribution to the cause of mission.”

Using Ludlow and Peabody made sense, given their recent experience with college planning and their Presbyterian connections. And, in a March, 1912 letter, Ludlow expressed a willingness to take on the Nanjing project, and offered to exempt from charge his own and his partner’s time, if not all design costs. But in a reply to Ludlow, dated June 4, 1912, Diffendorfer noted that Mrs. Cyrus McCormick had recently pledged $25,000 for a dormitory in Nanjing, and was eager to use her own architect. Ludlow’s response acknowledged the donor’s right to name the architect of the building she gave, but did doubt whether “it would be good policy for the Board to have him [Mrs. McCormick’s unnamed architect] also make the layout plan.” Ludlow thought the Board would be better served by a New York architect, easily reached from the Board’s New York headquarters. Diffendorfer’s late June reply stipulated that the matter would remain open, awaiting developments. In fact, however, Nettie Fowler McCormick seems to have seized the initiative. As the first of the big donors to the project, Mrs. McCormick seems to have earned the right to nominate the architect, and she wanted a Chicago—not a New York—architect.

In his 1937 biography of John E. Williams, vice-president of the University and fund-raiser-in-chief, W. Reginald Wheeler quotes from a Williams letter dated March 15, 1912 that reported on his most recent visits: “I saw Madame McCormick this afternoon. She gives twenty-five thousand for a dormitory of the College group. She was deeply interested in the whole scheme and in our plans.” The archive of the United Board of Christian Higher Education in Asia includes a brief letter of the same date, addressed to Williams, and signed “N. F. McCormick,” that confirms the gift, the first to underwrite the initial group of buildings of the University. Later, Mrs. McCormick, who was a much more generous philanthropist than her deceased husband had ever been and who gave substantial amounts to numerous overseas projects, was incensed at mistaken press reports that credited her with giving Nanjing a quarter-million dollars. The New York Times, for example, reported on December 22, 1913 that Mrs. McCormick “was to finance a large portion of the construction of a group of new buildings for the Shantung Christian University at Tsinan…and another group of buildings for the University of Nanking.” As she wrote in a January 15, 1914 letter, “I have made no such gift… I have promised one building to Nanking [a dormitory], and one to Shantung, not expensive buildings. This is all. I have no part in the other buildings” (although she did later contribute $10,000 toward the $30,000 Language School Building at Nanjing).

As Stella Virginia Roderick observed in her biography, Nettie McCormick had a deep interest in and appreciation of architecture (one of the reasons, perhaps, that her grandson Gordon himself became an architect): for instance, long before she became involved with the Nanjing project, she dealt with Louis Sullivan who designed a building she gave to Tusculum College and who also did some early work at Walnut Grove, her husband’s former home in Virginia. Mrs. McCormick’s archive is full of architects’ renderings for numerous projects she helped fund, so her insistence on using her own architects for the Nanjing project is no surprise, nor was it a surprise that Perkins, Fellows and Hamilton, who executed several buildings for her, including her Lake Forest home, received her confidence.

Correspondence surrounding the Nanjing University project confirms that Dwight Perkins won the commission through careful cultivation of Mrs. McCormick. Even before Fellows joined the firm, Dwight Perkins was exchanging correspondence with Mrs. McCormick, but in the period immediately leading up to the Nanjing commission, Perkins was particularly assiduous in his attentions. In the Nettie Fowler McCormick correspondence archived at the Wisconsin Historical Society is a letter from Perkins dated April 10, 1911 in which the architect noted Mrs. McCormick’s gift to Chicago’s Fourth Presbyterian Church and its new buildings. “Naturally,” Perkins continued, “we are interested in regard to the architectural commission, and write to ask what our chance is in this matter.” Another exchange of notes concerned Mrs. McCormick’s health; expressing thanks for his concern, Mrs. McCormick invited Perkins and his wife to accompany her to church, and then to join her at home for supper—which they did. Perkins shared architectural plans (for New Trier High School, for instance) with Mrs. McCormick, and she, in turn, tried to bring him into her circle of reading, at one point loaning him her copy of the Hibbert Journal, evidently as part of a discussion the two had had about war.

As the Nanjing project developed, Perkins made sure to touch base often with Mrs. McCormick. The McCormick archives contain early drawings of the dormitory she was donating (Front Elevation, May 27, 1912) as well as several attempts at laying out a new overall plan for the university (Group Plan, University of Nanking, May 27, 1912; Alternative Group Plan, May 27, 1912). Later deliveries included updated elevations (preliminary prints for the first and second floors of the dormitory, January 11, 1913; front and rear elevations of the dormitory, January 11, 1913; detailed drawings of doors and windows, January 11, 1913; and a cross-section of the north elevation (January 11, 1913). In addition, Perkins sent along a revised group plan (Long Scheme, University of Nanking, April 1, 1914; General Block Plan, University of Nanking, December 30, 1914; and a Topographical Map of North End of Campus, May 14, 1914. In brief, Mrs. McCormick received regular and detailed reports on the entire project. Her money as well as her experience with architects empowered her to propose to the university board that an architect be sent to China, as a May 9, 1913 letter from Dwight Perkins confirms: “During one of our conferences,” he wrote to Mrs. McCormick, “you suggested that some one of our firm should go to China and make a study of conditions to gather this information and to enable us to become more thoroughly equipped for this piece of work…The more we think of it, the more we are convinced that this would be a wise thing to do.” That mission fell to William Fellows.

William Kinne Fellows (1870-1948) was born in Winona, Minnesota, and grew up just blocks away from Seth Temple, who designed Grinnell’s Fellows House (no relation that I could establish). Also like Temple, Fellows attended Columbia University, graduating with an architecture degree in 1894, and, again like Temple, won a traveling fellowship to Europe in 1896. After his return to the U.S., Fellows entered private practice, partnering with George C. Nimmons in Chicago; the firm survived until 1911, specializing in large commercial buildings for clients like Sears, Roebuck and Co. Apparently it was Hamilton who recruited Fellows to the Perkins firm in 1911, where Fellows was responsible for numerous institutional designs, especially schools, for which the firm became well-known. When the partnership dissolved in 1925, Fellows continued to work on his own, although apparently without great intensity, since he had become very wealthy through some stock he owned. Fellows died in Chicago in 1948, his estate donating $560,000 to Columbia University to endow (in his name) traveling scholarships for young architects—like the fellowship that Fellows himself had won in 1896 (see New York Times, February 22, 1953).

By all accounts, Fellows was a gifted architect, but apparently he was also something of a loose cannon within the office; according to the recollections of Dwight Perkins’s son, Lawrence Bradford Perkins (1907-97), Fellows quarreled with his former partner, George Nimmons, because Fellows was uninterested in paying—or even maintaining—accurate bills. Fellows was “handsome, urbane, very talented, and bone lazy,” as Lawrence put it, but he was very skilled and deeply influenced by European trends—”Gothic ornament…dripped off his fingers,” the younger Perkins reported, with the result that later projects of the firm lost the prairie impulse that Dwight Perkins had first developed (and so brilliantly conveyed in the several structures at Chicago’s Lincoln Park and Carl Schurz High School).

Campus Plan of University of Nanking. Educational Buildings by Perkins, Fellows and Hamilton (Chicago, 1925), 144.

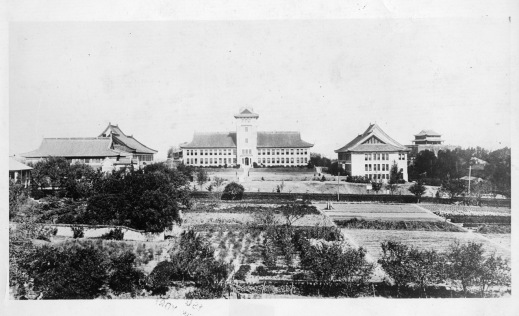

Nanking University, Main Quadrangle (ca. 1920). Photo courtesy China Christian Colleges and Universities Image Database (http://divdl.library.yale.edu/ydlchina), Yale Divinity Library.

After Perkins devoted several months to negotiation with the university board over the cost of sending Fellows to China, William Fellows left Chicago for China in late December, 1913. The March, 1914 issue of the University of Nanking Magazine enthusiastically welcomed Mr. and Mrs. Fellows and plans for the university he brought along. The differences between the early plans that Mrs. McCormick received in 1912 and 1913 and those subsequently developed make clear that Fellows’s visit to Nanking had a tremendous influence on the final design. The original group plan shared many basic ideas with the 1912 scheme of Cady and Gregory, with dormitories flanking the chapel and science building in one grand courtyard that headed a long axial orientation. But after having seen the site, Fellows opted for a much more interesting solution whose basic outlines may still be seen in today’s university campus, despite all the subsequent growth of the university.

Following a detailed topographic study of the site, Fellows proposed in his 1914 report to university trustees to isolate “the main college group on a system of terraces at the north end of the property…these form a series of ascending courts from a public road at the bottom… This places the Chapel and Library on the first terrace, about five feet above the road; the two Science buildings on a second terrace, about ten feet above the road; and the Administration building on a third terrace, about fifteen feet above the road…This arrangement gives the dominant position to the University group at the north end of the plan.”

A second emphasis of Fellows’s report fell on building materials. Fellows noted that, although China had plenty of building materials (with the exception of wood), “there is no building material easily available…in Nanking.” Having observed local brick production, Fellows found Nanking bricks “at best…soft, and deficient in bearing strength.” Building in brick requires mortar, but Fellows reported that “there is no local sand available,” nor, it seems, was any “suitable building stone…found in the immediate vicinity.” Nevertheless, he was able to recommend a series of solutions for building materials, and provide specific costs, the better to estimate how well donors’ funds matched actual building costs. University Trustees by resolution of April 27, 1914 endorsed Mr. Fellows’s report, and provided a list of preferences for building materials. For the walls, the trustees thought “Specially burned brick with marble trimmings” their least favorite solution, but it was, in fact, the ultimate choice. For foundations, the trustees hoped for concrete or local sandstone, city-wall brick as a third option—again, the alternative won the day. Something similar happened with roofing choices, the trustees expressing a preference for green or yellow glazed tile, but willing to accept concrete or slate. Despite these variations, there can be no doubt that, because Fellows had investigated all these options on-site, the architects and University trustees were on much firmer ground about their plans than they could possibly have been in the absence of Fellows’s sojourn in Nanking.

Henry Murphy, Foreign Languages Building, Nanjing Normal University (former Ginling College). 2011 photo.

The last part of Fellows’s report dwelt on style, bemoaning the failures of foreign efforts in China. “The foreign style has so far developed nothing worthy of imitation,” he asserted; “Foreign architecture as introduced into China through the Treaty ports from Hong Kong and the south has not one feature to redeem its stupidity. Transplanted Gothic, no matter how well it may be executed, looks out of place.” Fellows, from whose fingers Gothic designs fairly dripped (according to Lawrence Perkins), thought “it would be a worthy work to adapt the Chinese to their modern and changed conditions and still retain for them the beauty and individuality of their native art.” Writing about the Architecture of Christian campuses in China, Jeffrey W. Cody pointed out that the “Beaux-Arts method helped architects lay out their buildings within a spatial system that made coherent sense to them…[and showed a] predilection for symmetry and the creation of courtyard configurations…” Henry Murphy‘s plans for Ginling College may represent this finding best, but Bill Fellows’s plans for Nanking University certainly harmonize well with Cody’s analysis. The courtyard cluster, the use of transitions (via paths at Nanking), an axial orientation to the cluster, and relatively tall structures to anchor vistas—all these may be found in plans developed by Fellows for Nanking university.

Swasey Science Building, University of Nanking. Photo courtesy China Christian Colleges and Universities Image Database (http://divdl.library.yale.edu/ydlchina), Yale Divinity Library.

McCormick Dormitories, University of Nanking. Photo courtesy China Christian Colleges and Universities Image Database (http://divdl.library.yale.edu/ydlchina), Yale Divinity Library.

Other alterations followed, most a function of the availability of materials. One significant change was to abandon the idea of one large dormitory, and to use Mrs. McCormick’s gift instead to build two smaller buildings, the beginning of a residential courtyard. But once the dormitories went up, other structures soon followed. Thanks to the generosity of Cleveland’s Ambrose Swasey (1846-1937), a new science building was completed in late 1916, allowing Swasey and friends to attend the formal dedication in Nanjing, January, 1917. The administration building was the gift of two other Cleveland philanthropists—John L. Severance (1863-1936), famous for Severance Hall, today still home to the Cleveland Orchestra, and his sister, Elisabeth Severance Prentiss (1865-1944), who gave generously to Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Museum of Art. Fellows and Severance exchanged a series of letters, the basic thrust of which was Severance’s desire to trim the costs of the building, especially by deleting the tower. Fellows, however, held firm, insisting that the tower was crucial for water supply as well as aesthetics, and in the end his view carried the day, even if it did cost the Severance siblings another $15,000 over the $25,000 they each gave. Day Chapel, as it was called in the early correspondence, was later named Sage Chapel, thanks to a $25,000 gift from the Sage legacy by the New York Women’s Board. Bailie Hall, named for the university’s long-time agricultural specialist, Joseph Bailie (1860-1935), closely matched the Swasey Science Building on the opposite side of the courtyard, but was not completed until 1925, bringing the main courtyard near to completion on the eve of political turmoil that took the life of John Williams and did so much to interrupt the successful growth of the university.

John L. Severance (1863-1936), donor (with his sister, Paula Prentiss) of Severance Hall, University of Nanking.

Elisabeth Severance Prentiss (1865-1944), donor to Severance Administration Building, University of Nanking.

Severance Hall (Administration Building), University of Nanking. Photo courtesy China Christian Colleges and Universities Image Database (http://divdl.library.yale.edu/ydlchina), Yale Divinity Library.

***

Sage Chapel, University of Nanking. Photo courtesy China Christian Colleges and Universities Image Database (http://divdl.library.yale.edu/ydlchina), Yale Divinity Library.

Writing in the April, 1916 issue of Western Architect, Robert Craik McLean noted that “three early members of the [Chicago Architectural] club are now engaged upon the most notable works performed by ‘foreign’ architects in the history of the modern world.” And who were these architects? Walter Burley Griffin, by then deep in the struggle over what would become Canberra, was first on the list. The second architect whom McLean saw taking his Chicago experience abroad was Frank Lloyd Wright, then at work on the commission that became the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. The third Chicagoan whose art had crossed American borders and whom McLean grouped with Griffin and Wright was William K. Fellows, partner with Dwight Perkins and chief architect of the Nanjing project.

Perkins Eastman, Samuel Pollard Building, Johns Hopkins-Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies. 2011 photo.

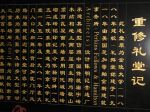

Commemorative Plaque in lobby of Auditorium Building (Former Sage Chapel), Nanjing University. Photo 2011.

Of course, McLean was writing nearly a century ago. But more recent developments have once again brought Perkins, Grinnell, and Nanjing back into contact. In 1987, Grinnell College signed the first of a series of agreements—recently renewed on the 25th anniversary—that linked the Iowa college to today’s Nanjing University, and has resulted in many tens of faculty from each school visiting the other, and has placed some fifty Grinnell College graduates in Nanjing, teaching at the university-affiliated high school. An even more intimate revival of old connections appeared in Nanjing where in 2001-2002 the University undertook a costly and very careful restoration of the former Sage Chapel under the direction of Zhao Chen and Leng Tian. Visitors to the newly-refurbished auditorium can see in the lobby a plaque that recognizes Perkins, Fellows and Hamilton. Finally, in 2006, Perkins Eastman, one of whose principals is Bradford Perkins, grandson of Dwight Perkins, designed a new building for the Johns Hopkins-Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies, thereby reviving the architectural legacy of Perkins, Fellows and Hamilton on the Nanjing University campus.

Recent Comments