Race and Ethnicity in the Rickers’ Grinnell—Part 2

Six Chinese Students in the Grinnell College Class of 1920: (L-R, top) Wen Chian Feng; Pao Shu Kuo;Liang-Chao Cha; (L-R, bottom): Chung-I Tseng; Ko-Nien Yang; Kuo-Neng Lei.

As noted in an earlier post, B. J. and Mabel Ricker did not have much occasion to encounter racial diversity in 1920s Grinnell. Although the Rickers did hire help at home—the city directory reported that Mary Elick was a “domestic” at 1510 Broad where she lived, and that James H. Daley was the Rickers’ “houseman,” although he lived at his own residence—their help was white, like that of their neighbors. Similarly, as Alice Renfrow reported, no blacks or Mexicans worked at the glove factory, despite the frequent advertisements to hire more help when the glove business was booming. But Ricker’s close association with Grinnell College—as an alumnus and, since 1910, a college trustee—did offer him some familiarity with racial diversity as it appeared on the college campus.

***

Over the years, an occasional Asian student studied at Grinnell College. Perhaps the most famous Japanese student at Grinnell was Sen Katayama (1859-1933), who graduated from Grinnell in 1892 and went on to found the Japanese Communist Party and to serve the Comintern in Moscow (where he is buried). But Asian students remained exceptional at Grinnell, at least until the 1916 establishment of Grinnell in China. The class of 1913, for instance, included Jiro Imada, a student from Hiroshima, Japan, and both Aquilino Carino (Philippines) and Pyn Muangman (Siam/Thailand) were part of the class of 1923.

In the years around 1920, however, Chinese students came to constitute the largest, most recognizable minority on the college campus. Even then, however, Chinese students matriculated at irregular intervals. The class of 1916 included only one Chinese, E. Hsuehcheng Hou, who hailed from the Shandong where Grinnell in China was headquartered. Apparently there were no Chinese students who graduated in 1917 and 1918, but the class of 1919 included three Chinese men (Tsu Lien Wang [Shanghai]; Chuang Lu [Dewang, Sichuan]; Kuang Chao Lu [Wuchang]), and at least seven were part of the class of 1920. Four of this group lived off-campus: Ching Tseng (Jiangsu) lived at 1233 Park; Wen Chian Feng (Chow Hsien [?Zhaodong, Xian?]) lived at 1033 Park Street with Fan Kuong, while Pau Shu Kao (Cheushu?) and Yu Pin Kuo (Hunan) lived at 1032 West. At least three more Chinese students appear in the college yearbook but not in the 1920 census or directory: Liang-Chao Cha from Tianjin; Kuo-Neng Lei from Kai-Hsien; and Ko-Nien Yang from Changsha. None were U.S. citizens, and all had entered the U.S. within the few years prior to 1920, probably only for purposes of attending college.

The class of 1923 counted just three Chinese students (Chieh Min Chang [Chaugh, Zhili Seng], Tsung Chin Chao [Gansu], and K. C. Wu (Kuo Cheng Wu [Beijing]), who went on to receive an honorary degree from Grinnell College and become an important part of Chiang Kai-Shek‘s Kuomintang. The following year a larger contingent from China studied in Grinnell: “Eaton” Kung Chun Tsai (Fuzhou); Jen Pei Shen (Beijing); Chi Chang Ma; Kai Yun Lu (Beijing); Shao Yu Liu (Beijing); “Durham” Chen Chang (Beijing) and Te Hsu Cheng (Nanjing). Yet another Chinese, Sin Chen, had been part of the class of 1924, but after only a semester in Grinnell he left for Columbia University business school. So young Chinese men were not unusual on the streets of Grinnell in the Rickers’ last years in town; not only was there a regular presence of Chinese men on campus, but several also boarded off-campus, and inevitably therefore had contact with town residents and businesses. But except through the college population, the men and women of Grinnell had scant reason to meet anyone from Asia. The sole exception to this generalization seems to have been Kim Fong, a 54-year-old Chinese man who reported to census-takers that he had entered the U.S. in 1899 and who in 1920 was operating a laundry on Broad Street (the 1920 city directory, however, does not include Fong).

***

The class of 1922 included no Chinese at all, but did include two black men: Mona Tappie Chie, an international student from Liberia, and Hosea Booker Campbell, an African American from Tallahassee, Florida. Chie had been born in a small Liberian village, and had then moved to Monrovia where he began mission school; with the intervention and help of one of his teachers there, he entered the U.S. in 1913, enrolling at Taylor University academy in 1914 and at Grinnell College in 1918. A Chemistry and Zoology major, Chie promised great things, but never graduated from Grinnell: after a lengthy illness in the spring of 1922 he died and was buried in Hazelwood cemetery. Hosea Booker Campbell, concentrating in History and Philosophy, attended Grinnell on a Julius Rosenwald scholarship. Upon graduation, he entered Harvard University, pursuing an advanced degree in history. Here he met John Hope Franklin and studied under Carter G. Woodson, a pioneer of African American history.

Gravestone for Mona Tappie Chie, Hazelwood Cemetery, Grinnell, Iowa. Photo by and courtesy of Bill Baumbach.

Overall, however, only a handful of blacks attended the college in these years. The class of 1913, for example, included J. Owen Redmon from nearby Colfax, while Alphonse Heningburg, native of Mobile, Alabama and a graduate of Tuskegee, was part of the class of 1924. Sebert Dove, native of Jamaica, was a classmate to Heningburg, and both were active in the newly-formed college Cosmopolitan Club—devoted to promoting “a friendly relationship between the foreign and the American students, and to unite them in a spirit of understanding.” Despite this noble sentiment and the efforts of the Cosmopolitan Club, Ricker and his north Grinnell friends will not often have seen African American students in town. Townsfolk were more likely to have noticed Mumpford Holland or Lee Renfrow, although these black men will have occupied only a small margin of the attention of prosperous, white Grinnell.

***

None of this indicates that Grinnell was insular. Indeed, the 1920 census reveals that a good part of the town’s population was foreign-born, including some of Grinnell’s most famous and well-off citizens. For example, both Andrew McIntosh (who married B. J. Ricker’s sister, Addie) and R. G. Coutts (who built Ricker’s brick home and whose several children attended Grinnell College) were born in Scotland and adopted Grinnell after immigration. Al Lindeen and John Anderson, building contractors who lived at 808 Summer Street, were both born in Sweden; Ole Bartinan and his wife Aagot had immigrated from Norway, while Anton Rohner and his wife Maggie were Swiss, operating a bakery in town. Daniel Berman, the junk dealer who lived at 803 Pearl Street, like his wife and children, was born in Russia, but, like many others in 1920s Grinnell, the Bermans made Grinnell their home, their ethnic difference submerged beneath racial similarity.

The college also attracted to town foreign-born faculty, including some of the its most well-known professors, several of whom lived in a cluster on High Street where the young B. J. and Mabel Ricker had first lived. Edward Steiner, for example, age 53 in 1920 and Rand Professor of Applied Christianity, had entered the U.S. in 1886 from Austria and been naturalized six years later; he and his wife lived at 921 High. Another Austrian, Edward Scheve, professor of music, was one year older than Steiner, but had immigrated in 1883 and claimed to have been naturalized in 1894 (although, in fact, once World War I began, Scheve required the college’s help in 1914 to confirm his citizenship). Scheve’s wife, Lina, German by birth (but Austrian according to the census), had arrived only in 1890 and she reported having gained American citizenship in 1896; in 1920 the Scheves lived at 914 High.

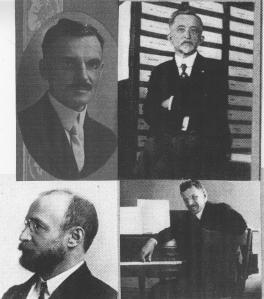

Foreign-born Faculty of Grinnell College (clockwise from top left): Eugene Lebert (French); Edward Scheve (Music); Elias Blum (Voice); Edward Steiner (Rand Professor of Applied Christianity).

Eugene Lebert (42), assistant professor of French, had immigrated from Nantes, France in 1906, and at the time of the 1920 census was still an alien; his wife, Frances (36), who lived with him at 931 High Street, had accompanied him to America, and she, too, remained alien. Elias Blum (38), instructor in voice, had immigrated from Hungary in 1891 and was naturalized eleven years later; Blum’s wife, Jennie (37), claimed German birth, moving to the United States in 1910. Several college faculty who themselves were America-born had immigrant spouses. John Stoops‘s first wife, Mary (54), for example, was Canadian, moving to the U.S. in 1886 and becoming a citizen in 1901. Similarly, Elsie McClenon (35), wife of mathematics professor Raymond McClenon, was German, but received American citizenship in 1912.

These European immigrants, however, caused less notice in Ricker’s Grinnell than did people of color. All white, the foreign-born faculty, like the foreign-born McIntosh and Coutts, were imagined to share the “determination, will power, self-control, [and] self-government” implicit in their race. Domiciled around the college, often in grand homes, these immigrants were not differentiated by race, and could interact freely with the town’s business and social elite, even if their incomes did not make them rich.

***

The situation was different with the Mexicans and African Americans, most of whom earned modest incomes and occupied modest homes on the town’s social fringe. Marked by the color of their skin and the inherited notions of race, these men and women interacted with white Grinnell only in very limited circumstances and from positions of financial and social disadvantage. Even men like B. J. Ricker, who were educated in a college founded by abolitionists and who as students themselves encountered fellow-students of color, seem to have inherited notions of racial difference. Could it have been an accident that Ricker’s glove factory never found it possible to hire someone like Alice Renfrow? And did Ricker, who graduated the year before Sen Katayama, and who therefore almost certainly knew him, and who, as a member of the college’s board of trustees helped oversee the enrollment of Chinese students and the foundation of Grinnell-in-China, see Asians as his racial and social equals? The Rickers’ adoption of Australian children showed them to have no bias against the foreign-born, and when in 1930 B. J. and Mabel helped their children return to Australia for a prolonged visit, they reinforced their sense of international awareness in an age when American immigration policies were becoming increasingly restrictive. But perhaps race proved a more difficult challenge, and the Rickers, like much of the rest of Grinnell of that time, implicitly accepted the advantages of being white.

Recent Comments